According to a recent report, Sweden, a nation known for its progressive education system, officials have recently decided to reinvest €104 million in printed textbooks. This move was prompted by growing concerns about the negative effects of excessive screen time on students’ learning and development. Research has shown that screen-based reading can lead to eye strain, reduced comprehension, and difficulty retaining information. Mathias Curl, Editor-in-Chief of The Indian Defense Review, highlighted this shift as Sweden’s acknowledgment that abandoning traditional methods too quickly, particularly for younger students, has long-term consequences. “The government now sees this as a misstep—ditching traditional methods too quickly without thinking about long-term consequences,” he wrote in his piece adding that understanding what you read and remembering it takes a hit when you’re staring at screens.

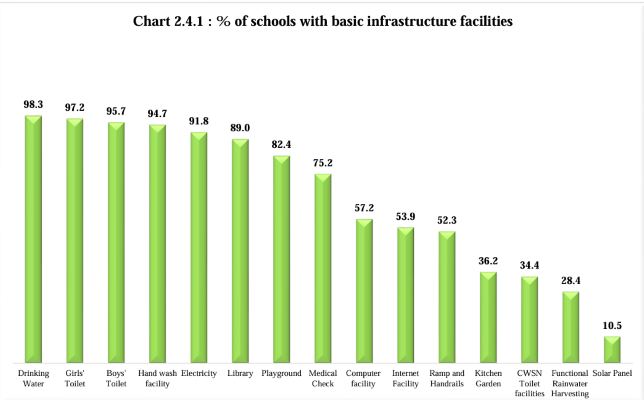

This decision in Sweden may offer useful lessons for India, where digital learning has seen rapid expansion. With only 57.2% of schools having functional computers and 53.9% with internet access, India faces its own digital divide, especially in rural areas. As India considers its digital education strategies, balancing the benefits of technology with traditional learning methods could be key to improving student outcomes across the country.

While both these reports serve as insightful and evidence-based ingredients for a policy discussion on school education in India, there is another equally significant input on ‘Phonics and a knowledge rich curriculum’ that country’s policy ecosystem needs to talk about. Spoken of by Sir Nicolas John Gibb, former Schools Minister, UK, who is involved in education policy making for over 20 years, there is ample evidence to show that lack of academic rigour, poor pupil behaviour, and a weak curriculum in schools put children particularly from the disadvantaged communities at more disadvantage. Sir Gibb was in Delhi for a conference (ARISE) last month (December 2024).

A successful model for India to examine is the UK’s approach to literacy, particularly the systematic use of phonics in primary schools. Sir Nicholas John Gibb, former Schools Minister in the UK, shared insights at a recent education conference in Delhi. Under his leadership, England’s education reforms between 2010 and 2024 focused on rigorous standards and evidence-based teaching methods. Key among these was the shift from multi-cueing methods (such as the Searchlights approach) to systematic synthetic phonics for teaching reading.

The results have been significant: England’s students now rank 4th in the world for reading according to the PIRLS study, with substantial improvements in international rankings for math and science as well. Gibb’s model included robust accountability measures, such as the Phonics Screening Check, which ensures that no child falls behind in early literacy. The UK’s commitment to a knowledge-rich curriculum, in contrast to the previous focus on competence-based skills, has helped elevate student performance across the board.

For India, adopting a similar phonics-based approach could address literacy challenges, particularly in government schools where foundational reading skills remain a concern. With only 57.2% of India’s schools having functional computers, a push for practical, effective literacy strategies could have far-reaching benefits for the nation’s young learners.

Speaking about a case study around usage of phonics in place of searchlight method in UK after he became schools minister, Nicolas Gibb said, “As a result of our reforms between 2010 and 2024, England is now fourth in the world for reading in the PIRLS study, we have risen from 27th in 2009 to 11th in Maths in PISA 2022 and from 25th to 13th in reading in PISA. In TIMSS England is now 9th in the world in Maths at Grade 4 and 6th in the world for Grade 8.”

Speaking about a case study around usage of phonics in place of searchlight method in UK after he became schools minister, Nicolas Gibb said, “As a result of our reforms between 2010 and 2024, England is now fourth in the world for reading in the PIRLS study, we have risen from 27th in 2009 to 11th in Maths in PISA 2022 and from 25th to 13th in reading in PISA. In TIMSS England is now 9th in the world in Maths at Grade 4 and 6th in the world for Grade 8.”

He added, “Teachers are now writing, blogging and podcasting, setting up their own state schools, attending ResearchEd conferences founded in England by the great Tom Bennett. It is for that reason that I remain confident that our reforms will last, no matter who is in government; and why I strongly believe that they are transferable to any country with the same determination to raise academic standards in their schools, particularly for the most disadvantaged.”

When Conservative Party came into office in 2010 in UK, it removed the competence-based curriculum and established a fundamental overhaul of both the primary and secondary curriculum. As a shadow minister Gibb had evidence from cognitive science that flatly contradicted the received views in the education world that knowledge is less important than teaching skills such as critical thinking, problem solving and creativity. “What is now clear is that only by having knowledge in your long-term memory can you perform those high-level intellectual activities. This evidence undermines the whole reason behind the competence-based curriculum introduced by the Labour Government in the UK in 2007 which itself was built on principles which already prevailed in most state schools,” he told at the conference.

“When we came into office after the May 2010 general election, we changed the National Curriculum to require teachers to use systematic synthetic phonics in the teaching of reading; we funded schools to buy phonics resources and training; we changed the Teachers’ Standards so that to qualify as a primary school teacher you had to be able to teach reading using systematic synthetic phonics; we changed Ofsted inspections so that inspectors heard the weakest readers in the school read. And most importantly we introduced the Phonics Screening Check.

Each 6-year-old child reads the 40 words, one-to-one with their teacher. The pass mark is 32 correctly read words out of 40. If a child doesn’t reach 32, they are required to sit the Check again the following year, ensuring no child slips through the net with their reading struggles unnoticed. Of the 40 words in the Check, 20 are false words, designed to ensure children can sound out new words using phonics.

Results went from 58% in 2012 (33% in the pilot in 2011) to 82% in 2019, just before Covid. Then slipped but recovered in 2023 to 79% and this rose again to 80% in 2024. There’s a 92% achievement if you include the results of the year 2 tests. There is more to do – we should be achieving 92% in year 1 or even 95%. Several hundred schools reach 100% each year.

And it’s working – every school in England is now using phonics, even if some could do it better. Gone is the multi-cueing or Searchlights approach to children which essentially encourages children to guess the word instead of reading it.

And we know it’s working because in the most recent PIRLS study (Progress in International Reading Literacy) England came fourth in the world out 43 countries that tested children of the same age. Behind just Singapore, Hong Kong and Russia.

We also used strong accountability measures such as performance tables of schools’ results – SATs tests in Reading, Writing and Maths taken at the end of primary school and the GCSE results. On a school-by-school basis we publish the figure for the proportion of pupils at the school reaching or exceeding expected standards.

Scotland adopted a competence-based curriculum called ‘The Curriculum for Excellence’ which downplayed the importance of knowledge, and focused instead on high-order intellectual skills, leaving teachers to determine the knowledge content. Wales soon followed with a similar competence-based curriculum. And here are the interim results:

You can see that how Scotland and Wales have both slipped dramatically down the PISA league table for maths and science. Wales has also fallen in reading. It’s interesting that Scotland has risen in reading. Scotland doesn’t take part in PIRLS but I believe the fact two key RCTs in phonics took place in Scotland – Clackmannanshire and West Dunbartonshire – has impacted on the teaching of reading throughout Scotland.”

While international models offer valuable lessons, India’s own unique challenges in education reform must be acknowledged. Prof. Govinda, Distinguished Professor Council for Social Development & former vice-chancellor NEIPA who is also the author of The Routledge Companion to Primary Education in India from Compulsion to Fundamental Right, during his recent 21st C.D. Deshmukh Memorial Lecture, highlighted a critical issue in India’s education system: the stark divide between “Grand Schools” and “Little Schools.” The Grand Schools cater to the children of the elite, with high resources, English-medium education, and access to modern teaching tools. However, these schools represent only a small fraction of India’s educational landscape. The remaining 14 lakh schools, referred to as “Little Schools,” are often underfunded and lack the necessary resources, which results in significant educational disparity.

This divide reflects the historical influence of Lord Macaulay’s educational reforms during British rule, which prioritized the education of the elite and ignored the masses. Despite 75 years of independence, this legacy still affects the quality of education available to the majority of Indian students. Prof. Govinda’s metaphor of the “broken mirror” illustrates the fractured nature of India’s education system, where some students thrive while many are left behind.

This divide reflects the historical influence of Lord Macaulay’s educational reforms during British rule, which prioritized the education of the elite and ignored the masses. Despite 75 years of independence, this legacy still affects the quality of education available to the majority of Indian students. Prof. Govinda’s metaphor of the “broken mirror” illustrates the fractured nature of India’s education system, where some students thrive while many are left behind.

Coining this scenario as ‘The Grand School and the Little School: A Fractured Perspective’, Prof Govinda said, “Why did we not seriously engage in the task of educational reconstruction in the last 75 years? Why have we remained so indifferent towards structural reforms in education? The short answer is that fundamentally we remain Macaulayists. The main principle advocated by Macaulay was to divide schools between the class and the mass, and the Government to focus on the education of elites. I believe we have been willingly or unwillingly reviving and embracing that division in our school system. Contemporary events during the during the last few decades resemble a repeat of what happened in history soon after Macaulay minutes were adopted by the British.

Most of these Grand Schools are private self-financing high fee charging schools affiliated to CBSE or ICSC or in recent years to the IB System. Children in these schools study through English medium. There are only around 27000 schools in this category in the entire country. We can add a few thousand schools affiliated to State Boards and the Kendriya Vidyalayas in this category of Grand Schools. Yet, this category of schools constitutes only a small fraction of the total number of schools in India which is 1.5 million. On the other hand, the remaining approximately 14 lakh schools are ‘the little schools’, most of which do not go beyond the primary level. These schools are the complete opposite of the ‘Grand Schools’ in every aspect of resources. In reality, the “little schools” are similar to the vernacular primary schools of the colonial era acting more like filters as many children never move beyond these fragmented schools.”

In conclusion, while India’s educational landscape faces many challenges, these lessons from Sweden and the UK, along with a deeper understanding of the internal divides within its own system, offer a roadmap for meaningful reforms that could impact millions of students across the country.

As policymakers in India look to the future, they must draw on the lessons from these international examples and consider the unique needs of their diverse student population. Education reform in India is not just about upgrading systems but also about creating an inclusive, knowledge-based framework that serves every child, regardless of their background.

-Autar Nehru