By Autar Nehru

The political economy of education is undergoing a paradigm shift to benefit a certain kind of alliance. That is at least what some seasoned observers have started to believe after analyzing the announcements by the Finance Minister on education sector in the union budget 2021-22.

The massive 6% reduction in the budgetary allocation over the previous year which the education ministry termed as ‘rationalization’ on account of the Covid exigencies is in fact seen as a pattern of according a low priority to public education. The arithmetic of education budgets in India is not that simple. Spending on education, which has been stagnating at 2.8% of GDP for past several years, has marginally gone up to 3.3-5% in last two years (2019-21). The union government share is just 0.49 % and this year it has come down to 0.42%. The bulk spending on education comes from state budgets. However, here is a catch. Samagra Shiksha Abhiyan, the flagship centrally sponsored Integrated scheme for school education, which is the major support scheme for functioning of schools in the country is being shared between centre and states in the ratio of 55: 45 (90:10 for NE states). The funds for the scheme in the budget have been slashed from Rs 38,751Cr in 2020-21 to Rs 31,300 Cr this year. Most of the states, which have to match the allocation, are in dire conditions as their revenue position has worsened after pandemic and non-receipt of tax shares. There are more than half a dozen special category states, where education spending is anyway lesser. So, naturally spending on education will face a further cut.

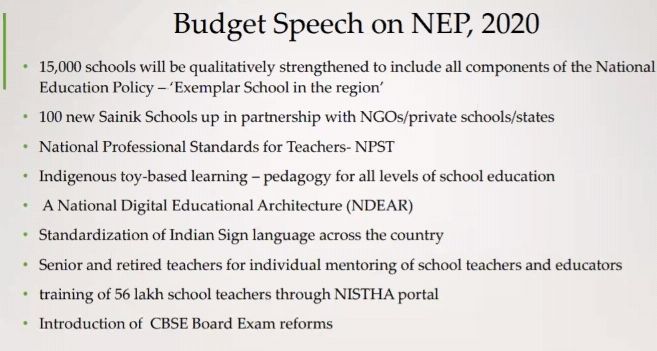

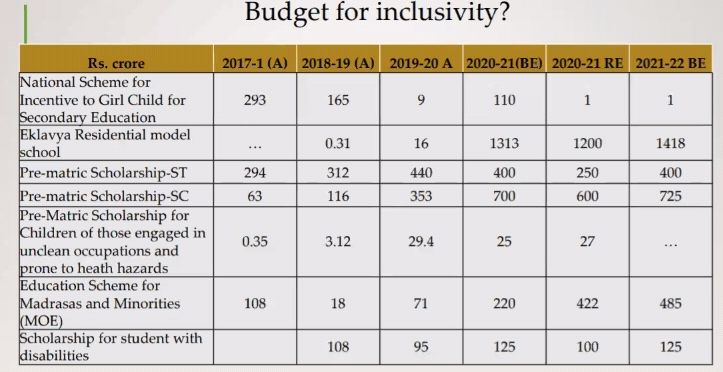

The impact of school closures due to Covid19 pandemic has changed the education landscape everywhere. Almost an academic year has been lost. In India an estimated 20 million children were not able to join online education and most of them belong to vulnerable sections and are on risk of dropping out for good. The other 40 million though had some kind of online learning engagement still need remedial education and mentoring. So, everybody was looking forward to a kind of ‘covid rehab’ package in the budget, but ironically the budget made it sound oblivious as if nothing has happened. Instead, the budget announced setting up of 100 new Sainik schools (34 schools already exist) and 750 new Eklavya (model residential) schools when the already sanctioned schools of the past have not taken off (only 285 Eklavya schools out of 566 sanctioned are functional in some form in tribal areas.)

The undoing of the impact of covid on school infrastructure ranges from repairs to sprucing, teacher recruitment, strengthening of special training program (STP), WASH & hygiene, enrolment and remedial education and even provision of devices and IT infra. The plight of girls in covid has been reported by several surveys from losing study time to household chores to marriages and even trafficking and yet National Scheme for Incentive to Girl Child for Secondary Education was buried in this budget.

So, absorbing covid impact should have been prioritized. But what attracted FM’s temptation was announcing 15000 ‘exemplar schools’ to include all components of the NEP 2020. It is like nothing when you talk of 15 lakh schools. Ashok Agarwal, education activist and president of the All India Parents’ Association slammed the idea of exclusivity with creation of a new school category while discriminating with the rest of children through these 15000 schools.

According to Prof Muchkund Dubey, former foreign sectary and president of Council for Social Development, New Delhi there is a long history of such initiatives. Citing the announcement of 6000 model schools including 2500 under PPP mode by UPA government under Dr Manmohan Singh, Prof Dubey referred to failed negotiations as the private players were keen on transfer of funds and that too to the tune of 50 times the government estimates.

The national education budget is almost entirely funded (97%) by education cess since it was levied in 2006 as a supplement to the budgetary allocation. And therefore, whatever has been allocated is subject to economic recovery and tax collections. “The flows are extremely uncertain. The mobilization of revenue had been falling before the covid and in the pandemic that fall has double to about Rs 4 lakh crore. This is a difficult situation and demand needs to be factored in,” said Prof Praveeen Jha, Professor of Economics at JNU who specializes in education economy. According to him the challenges is further aggregated by the fact that 80% of population has seen loss in income over the last 5-6 years and covid has impact livelihood of 70-80% although some have started recovering. Citing All India MSME Association claims, Prof Jha said that already 1/3rd of MSMEs might have vanished and another 1/3rd is struggling hard. “I am deeply distressed as I feel there may a generation loss from education system and its impact on our social geography could be on its fault lines,” he added.

India has ranked 94th out of the 107 assessed countries on the 2020 Global Hunger Index (GHI), with a level of hunger that is categorised as ‘serious’. In the previous budget Under the Saksham Anganwadi and Mission Poshan 2.0, the government subsumed four existing centrally sponsored schemes of umbrella Integrated Child Development Service (ICDS) — Anganwadi Services, Poshan Abhiyan, Scheme for Adolescent Girls and the National Crèche Scheme. This too has seen a massive cut in budget allocation.

“Unfortunately a narrower vision has taken root in the Government. The ministry of education appears to be just a post office and at best ministry for 20K CBSE schools. The schemes are not properly planned or discussed, we hear them only from the finance ministry,” said Prof R Govinda, former VC NUEPA currently distinguished professor at CSD.

Observers see the developments in the larger context of a massive push towards privatization and harnessing a political economy (corporate + hindutva alliance) where mass education will shift to skill development for youth to fit into various layers of economy. Prof Muchkund Dubey for instance feels that part of the blame rests with the mainstream economists who have weaved a wrong narrative by terming allocations for social sectors as give always and not recognized social sector investment in its developmental and economic role.

Education budgets and plans must reflect the reality and tame the challenges and not amplify them further. One hopes that economic recovery which has just begun provides more revenue to the Government and with it wisdom returns to the establishment and we see undoing of the reduction in the revised estimates during midyear review.

(The quotes and background of the article is based on the inputs from RTE Forum’s webinar on budget hosted on Feb 5, 2021)